Creeping toward quotas

Why the latest family planning measurements threaten to erode women’s agency and contain ominous echoes of past (and present) coercive practices.

When family planning groups speak to the public, they describe hundreds of millions of women desperately seeking contraceptives but cruelly denied access to them. When they speak to policymakers, they talk about poverty reduction, and lives saved.

But when talking to one another at family planning conferences or in the pages of technical journals, they speak of a very different problem: low demand.

After all, the idea that over two hundred million women lack access to contraceptives is massively exaggerated. Many of the theorized “lives saved” by contraceptives would in fact be lives averted. Furthermore, the tenuous claim that a “demographic dividend” would supercharge a developing country’s economy depends first and foremost on people actually using the contraceptives in the first place. And that brings us back to lack of demand.

The U.S.’s Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), which provides the survey data from which the so-called “unmet need” for family planning is derived, asks women with purported “need” the reason they don’t use contraceptives. In survey years 1986-1990, only 4% of respondents cited lack of access, while a quarter reported a lack of knowledge about family planning methods. In the latest survey round, 2006-2013, lack of access accounted for 4-8% of responses, while the proportion claiming lack of knowledge had shrunk down to a mere 1-6%.

During the past two decades, women around the world have become very aware of contraceptives, which suggests that those not using them are a) more likely than their pre-1990 counterparts to have made an informed decision in that regard, and b) a tougher audience to convince to use them.

Fueled by concerns about overpopulation, family planning programs have a well-documented history of coercive practices, from forced abortions, forced sterilizations, and numerical quotas that tied financial and other incentives to “performance” in using contraceptives or recruiting other new users.

In response to the resulting backlash, family planning groups changed their message to one of making contraceptives “accessible” and “available,” with an emphasis on things like quality and method mix, and the elimination of “barriers” – including the ones in women’s own heads. In light of that, it’s a bit surprising to see a recent article referring to “the delicate balance between protecting unfettered access and preventing abuse, and […] that fine line between encouraging and coercing.” Similarly, another Guttmacher-published article stated, “[d]efining coercion or coercive actions too broadly could incriminate all family planning programs”.

On paper, it’s about access, but in reality, it’s all about use. USAID’s Ellen Starbird recently spoke at a family planning conference in Indonesia. The Guardian reports:

“Starbird added that it was important to get “strong outcome indicators” in the SDGs. The indicators, which will be used to gauge progress towards meeting the goals, are still under discussion. One of the proposed benchmarks is to meet at least 75% of demand for family planning by 2030. “What gets measured, gets done,” said Starbird.

I’ve recently written about the problems with the proposed “satisfied demand” indicator, namely that it takes all the existing weaknesses of the “unmet need” indicator and ties them to contraceptive prevalence, thus making it more difficult for a country with low levels of contraceptive use to perform well.

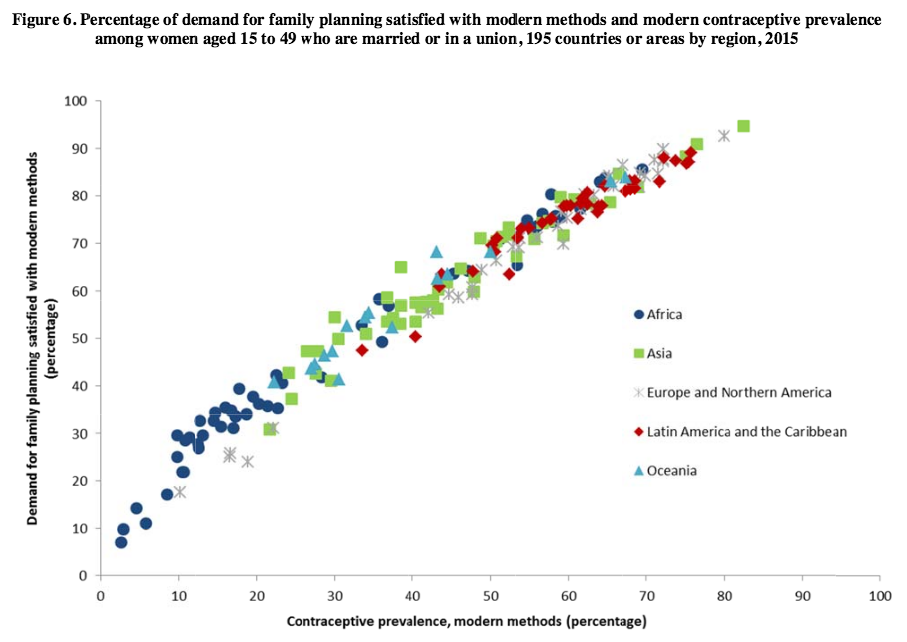

To illustrate, this is a graph from a recent publication of the Population Division of the UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs:

Notice the almost-linear relationship between “demand satisfied” and contraceptive prevalence – that’s not accidental, given that prevalence occurs in both the numerator and the denominator of the definition of “demand satisfied.”

In theory, a country with low contraceptive prevalence and low-to-zero “unmet need” could meet Starbird’s 75% benchmark. But in practice, based on existing country data, none of the 65 countries at or above that goal has less than a contraceptive prevalence rate of 56% (the average among those countries is 66.1%). And given the fact that most women with “unmet need” have no stated desire to use modern contraceptives, it is highly deceptive to characterize it as a “need” at all, much less a “demand.”

Assuming they are based in accurate data, contraceptive prevalence rates are not a terrible indicator in that they attempt to measure actual behavior without making a value judgment about it. “Unmet need” is a bad indicator because it misconstrues survey data to imply that the women surveyed will actually use contraceptives if they are available. But “demand satisfied” is a terrible indicator because it ties the two together in a way that measures access only in terms of use. To perform well, governments will have to find ways not only to satisfy a purported demand, they will have to create it first.

And that’s where the “delicate balance” and “fine line” between empowerment and coercion gets increasingly blurry.

View online at: https://c-fam.org/turtle_bay/creeping-toward-quotas/

© 2025 C-Fam (Center for Family & Human Rights).

Permission granted for unlimited use. Credit required.

www.c-fam.org