How to improve maternal and child health initiatives: measure real results, not hypothetical ones

It’s hard to question the motive of programs seeking to end preventable maternal and child deaths in developing countries. These efforts enjoy global support, and why not? Saving the lives of poor pregnant women and their babies is a noble goal.

And so, in the interests of encouraging the pursuit of that goal, I have a piece of constructive criticism for policymakers working to implement and scale up the interventions that help the most people: get some better ways to measure progress.

“Deaths averted” is a frequently-used indicator, broken down by categories like maternal, newborn, and child deaths averted. In news reporting and general discussions of progress made, “deaths averted” is often paraphrased as “lives saved.”

At surface level, that sounds like good things to measure — the whole point of these initiatives, after all, is to avert preventable deaths. But here’s the problem: it’s a lot harder to count events that don’t happen than those that do. When a mother dies in childbirth or a baby dies in infancy, you can count it. But is it reasonable to call every surviving woman and child a death averted? Not if you want to keep track of what you can claim credit for: even in the poorest settings, some proportion will survive without foreign aid assistance.

So how do you go about measuring averted deaths? You have to start with a good understanding of the area you’re serving: what are the starting rates of maternal mortality and child mortality, as a function of the number of live births. Then, you track how those ratios change over time, and hopefully see significant improvements corresponding to your interventions. As a general principle, it’s reasonable to expect that a figure for maternal deaths averted should correspond to a similarly-sized population of women who survived pregnancy and labor, and your figure for newborn deaths averted should imply a corresponding group of surviving newborns.

The problem is that “deaths averted” calls for numbers, not ratios, and since they are numbers of events that don’t happen, they are not anchored to any concrete reality. And that leaves the door wide open for manipulation.

To give an example, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) released a report in 2014 titled Acting on the Call: Ending Preventable Child and Maternal Deaths, which set a goal of ending preventable maternal and child deaths by 2035.

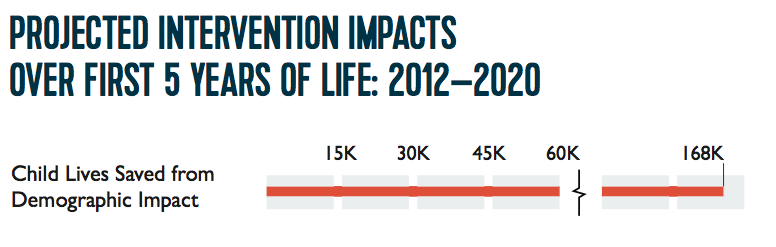

A look at Acting on the Call reveals what the U.S. government thinks it means to save lives. It gives a series of reports outlining interventions for specific countries. This comes from the first one, which is on Afghanistan:

Check out that fine print there. To make one thing abundantly clear, family planning does nothing for a woman in labor or a newborn child. If you’re pregnant but anemic, or newborn and preterm, contraceptives will not help you. But, say family planning groups, what about the benefits of birth spacing? Even if you want to make the point that the public health impact of more time between births should be measured—perhaps as a separate indicator—there is no earthly reason why this bit should be included:

A footnote helpfully points out:

“Demographic impact is the projected impact of family planning interventions on reducing the number of deaths due to fewer unintended pregnancies.”

In other words, infant deaths are being averted by averting the conception of said infants. This is then inexplicably paraphrased as “lives saved.” (I’ve written about this phenomenon before: “The Life You Save May Be an Exaggeration”.)

It’s truly mind-boggling how cynical this statistical sleight-of-hand really is. Family planning groups are patting themselves on the back for “saving lives” by preventing lives from being lived: the only future they see for those unintended pregnancies is a dead infant. But their prediction of infant deaths is achieved simply by multiplying the number of unintended pregnancies that result in births by the current infant death rate in the area. Not all infants die – some go on to live long, healthy lives, even the ones whose lives began in an unintended pregnancy. Oddly enough, nobody is calling for indicators on “first days of school averted,” “careers averted,” or “marriages averted.” They aren’t even claiming credit for the deaths from cancer or Alzheimer’s in later life that are averted by family planning.

Here’s the thing: it would be very easy to make our roads safe: just prohibit anyone from driving on them. Traffic fatalities could be eliminated overnight. Likewise, deaths in childbirth and infancy in Afghanistan could be eliminated if only pregnancy were eliminated. But nothing about doing that would make it any safer to be that woman who does get pregnant or that infant who is born. We owe the women and children of Afghanistan better than to tell them on their deathbed, “if only you’d used a condom,” or “if only you’d spaced your births more.”

And so, a request to all the people of good will who are working to improve maternal and child health around the world: Ensure that measurements of maternal deaths averted are tied to actual maternity and not its avoidance. Ensure that measurements of newborn lives saved involve actual living newborns. If you want separate indicators to measure family planning, keep them separate.

Finally, in developed countries, we pride ourselves on delivering good health outcomes for moms and babies, even if the pregnancy was high-risk or if complications ensued. Not every death is avoidable, but averting lives to avert deaths is the coward’s way out. We can—and should—do more.

View online at: https://c-fam.org/turtle_bay/improve-maternal-child-health-initiatives-measure-real-results-not-hypothetical-ones/

© 2026 C-Fam (Center for Family & Human Rights).

Permission granted for unlimited use. Credit required.

www.c-fam.org