UNFPA calls on “all stakeholders” to increase pressure on abortion

WASHINGTON, D.C., March 1 (C-Fam) Like many UN agencies, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) walks a fine line on the issue of abortion. Its mandate does not include promoting abortion or changes to its legal status, a fact that its supporters often cite when urging the United States to fund it. Nevertheless, like many UN entities, it has a history of exceeding its mandate, and many of its wealthier donors want it to go further.

So, if a UN agency is precluded from overtly pressuring countries to change their laws regulating abortion, it must rely on more indirect tactics, such as rallying pro-abortion governments to exert pressure on their fellow nations.

Within the UN human rights system, there exists a mechanism called the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), in which UN members review one another’s human rights records and offer specific recommendations for improvement. Civil society organizations and other stakeholders can also submit shadow reports. A cycle of the UPR, in which all 193 countries undergo a review, takes four and a half years to complete. The third cycle is currently ongoing.

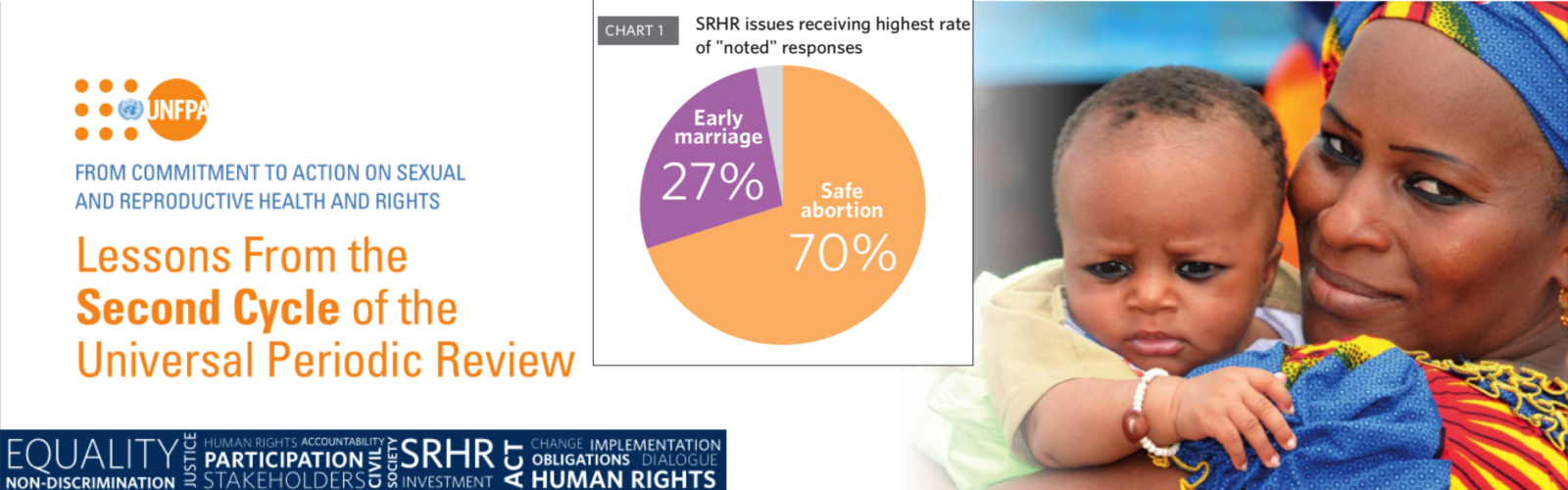

Recently, the UNFPA released a report summarizing the results of the second UPR cycle, which lasted from 2012 to 2016, with particular attention to topics designated as relating to “sexual and reproductive health and rights” (SRHR). With regard to abortion, UNFPA observed that the number of recommendations urging countries to liberalize their laws increased from 37 to 124 between the first and second UPR cycles. However, the report signaled disappointment that the number was not greater by calling on “all stakeholders” to increase reporting and recommendations on “SRHR issues that have received less attention within the UPR thus far,” including abortion.

Recommendations in the UPR can be either “accepted” or “noted” by the recipient country. The UNFPA reported that recommendations about “safe abortion” received the highest rate of “noted” responses among all SRHR issues—70%.

UNFPA titled the report “From Commitment to Action on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights.” This obscures the fact that SRHR as a concept is not universally accepted, and there are no global commitments that include it. Many of the issues UNFPA describes as components of SRHR are the subjects of international agreement. This includes women’s empowerment and participation, maternal health, and efforts to end domestic violence and human trafficking. However, issues related to abortion, sexual orientation, and gender identity have a far more controversial status in international debates.

But by conflating existing commitments on specific issues to a broad commitment to SRHR, UNFPA seeks to redefine the human rights obligations of UN member states, and encourage other stakeholders to take up the cause.

For decades, unaccountable UN experts have exceeded their mandates and pressured countries to change their laws on abortion. The UPR differs from other UN human rights mechanisms in that it facilitates member states talking to each other, instead of experts and committees talking to them. This provides a clear insight into where there is broad agreement between countries and regions, and where there is not. What UNFPA’s analysis inconveniently proves is that when it comes to abortion, there is no consensus—much less commitment—regarding its status at a global level.

View online at: https://c-fam.org/friday_fax/unfpa-calls-stakeholders-increase-pressure-abortion/

© 2025 C-Fam (Center for Family & Human Rights).

Permission granted for unlimited use. Credit required.

www.c-fam.org