Analysis Shows Only a Tiny Number of UN Member States Preoccupied with Homosexuality

WASHINGTON, DC, March 31 (C-Fam) A new analysis of the UN human rights monitoring system shows a universal preoccupation among experts but only a tiny number of member states with the controversial issues of abortion and homosexuality.

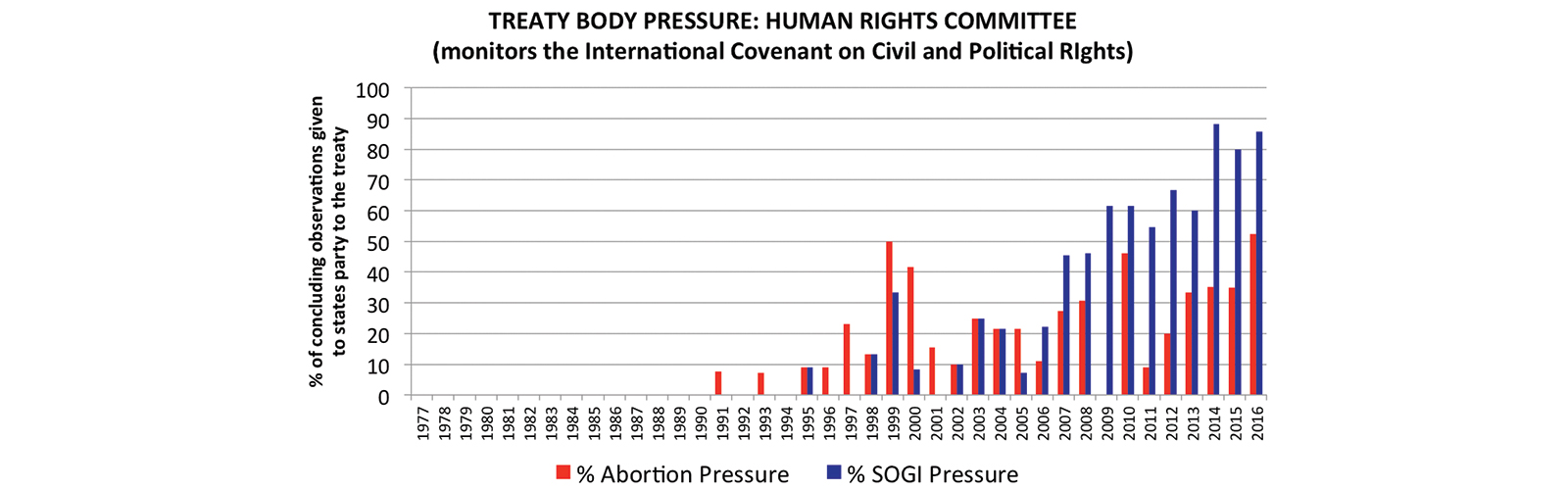

The data reveal that over half of the recommendations made by UN human rights treaty monitoring bodies included pressure on countries to liberalize their laws on abortion and sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) even though neither terms appear in any UN human rights treaty.

The Human Rights Committee, which monitors the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, was the most aggressive on SOGI, which appeared in eighty-five percent of its observations last year.

By contrast, a relatively new process called the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), where UN member states review each other, shows the abortion and SOGI obsession lies with a small number of mostly western countries. Over ninety percent of pressure on those two issues in the UPR came from fewer than 25 countries, respectively. Like the text of the UN’s binding human rights treaties, the vast majority of the 193 UN member states have remained silent on these divisive issues.

There is a longtime disconnect between the words in the treaties, the intentions of the states parties to the treaties and these treaty monitoring bodies. Not only do the treaties omit any mention of these issues, but the proposed inclusion of abortion and “sexual rights” in UN negotiations continues to cause gridlock and lack of consensus. In an attempt to bypass the need for agreement, these bodies of experts have been busily working to set their own standards—and hold the world accountable to them. These nonbinding opinions are then welcomed as “authoritative” by activist groups that share their goals.

Every jot and tittle of the UN’s human rights treaties were meticulously negotiated by member states, then carefully weighed by each nation considering ratification. Once a nation is bound by the treaty, it must submit periodic reports to a treaty monitoring body, which in turn gives recommendations for improved compliance. That is the process.

In the mid-1990s, several UN agencies and treaty bodies formulated a strategy to reinterpret human rights instruments to include these controversial issues with the view that they could force governments to change their laws. In a 2007 white paper “Rights By Stealth,” Dr. Susan Yoshihara and Dr. Douglas Sylva detailed the strategy from a decade later, revealing how this approach has undermined the entire human rights concept and led to increased distrust of human rights language from many UN member states.

Ten years later, quantitative analysis of several treaty bodies’ recommendations reveals that the pressure has only further increased.

Meanwhile, the definition of the family from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights has come under attack by those seeking to redefine the family from the natural and fundamental group unit of society to an open-ended structure taking “various forms.” To achieve this end, not only must radical new interpretations be read into treaties, but a founding document of the UN must be pushed aside or stripped of its authority in favor of a far less universal notion of human rights.

View online at: https://c-fam.org/friday_fax/analysis-shows-tiny-number-un-member-states-obsessed-homosexuality/

© 2025 C-Fam (Center for Family & Human Rights).

Permission granted for unlimited use. Credit required.

www.c-fam.org