WASHINGTON, D.C. June 20 (C-Fam) C-Fam’s massive human rights database tracks the ways in which human rights mechanisms are used to pressure countries to liberalize their abortion laws and legally recognize and promote gender ideology. The database, which went online last year, also reveals the ways in which this pressure has grown and changed over the years.

Abortion officially entered UN policy at the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), although attempts to enshrine it as an international human right failed. Yet even prior to that compromise outcome, the treaty monitoring body for the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) had taken an interest in the issue.

Shortly after the treaty came into force in 1981, the CEDAW Committee regularly posed questions to state parties about the practice and legal status of abortion. Immediately after the ICPD, however, the committee’s approach shifted. In its 1994 review of Colombia, the committee said “women in Colombia should fight for the legalization of abortion” to reduce maternal mortality due to illegal abortions. The next year, its review of Peru called for the country to “review its law on abortion” and “consider more expansive use” of exceptions for the health of the mother.

Not only did the CEDAW Committee’s pressure on abortion intensify, despite there being no mention of it in the treaty itself, but other treaty bodies started to do the same. The Human Rights Committee, which monitors the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) told Tanzania in 1998 to conduct a review of its abortion laws, and in 1999, its review of Chile included calls to make exceptions to its ban on abortion.

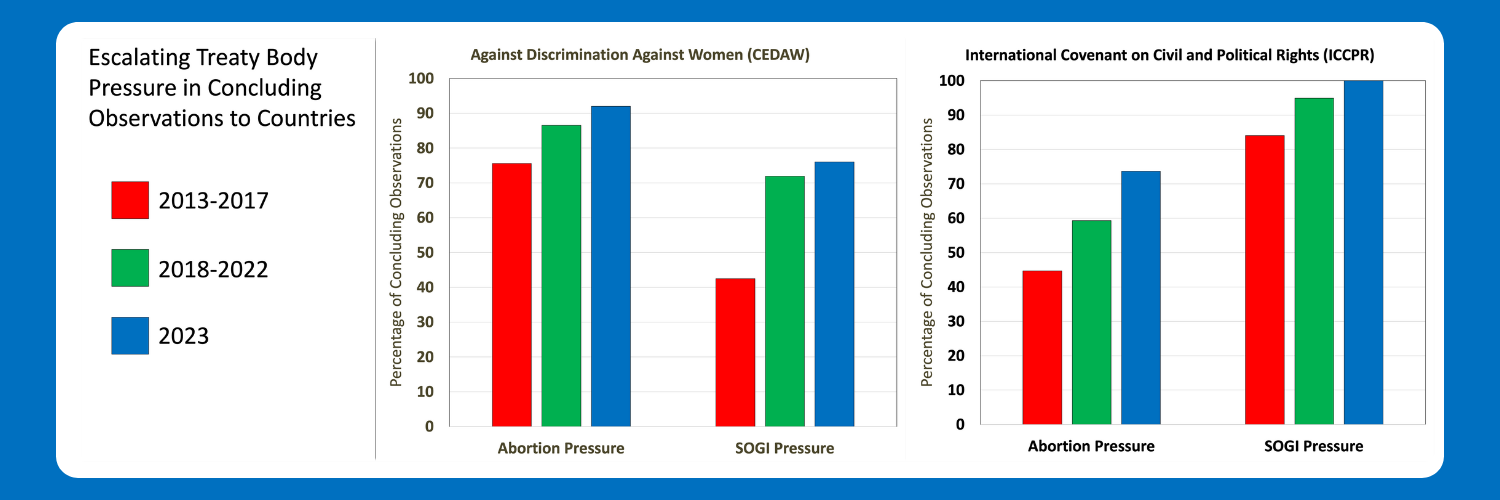

In the last decade, these and other treaty bodies have become increasingly aggressive on abortion, led by the CEDAW Committee, which pressured countries on abortion in over 90 percent of its reviews conducted in 2003.

Pressure on sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) gained traction later than abortion across the treaty bodies, but have since become even more prevalent than abortion. In 2023, every single country report by the Human Rights Committee included SOGI pressure. Instances of pressure include calls to decriminalize homosexuality, include SOGI categories in antidiscrimination laws, conduct public awareness campaigns to promote SOGI acceptance, and, finally, enshrine legal recognition of gender change and same-sex marriage and adoption.

For example, the Human Rights Committee’s 2024 review of Pakistan called for decriminalization of consensual same-sex relations between adults but also expressed opposition to legislative initiatives to “criminalize the provision of gender-affirming healthcare.” In its 2018 review of Bulgaria, the committee ordered the country to “fully recognize the equality of same-sex couples” with regard to marriage and the adoption of children.

As with abortion, there is no language about SOGI in any of the core UN human rights treaties, but that has not stopped all nine of their monitoring bodies to take up the issue of SOGI in their national reviews, and almost all of them to pressure countries on abortion.

These reviews are not binding, but they have been cited by activist courts in countries when changing their laws. They also have served as a source and justification for UN agencies that quote them as authoritative human rights standards. A major example of this is the human rights annex to the World Health Organization’s 2022 abortion guideline, which justifies its extreme stance mainly in opinions that originated with the treaty bodies.

View online at: https://c-fam.org/friday_fax/c-fam-database-shows-increased-treaty-body-pressure-on-abortion-gender/

© 2026 C-Fam (Center for Family & Human Rights).

Permission granted for unlimited use. Credit required.

www.c-fam.org