WASHINGTON, D.C., March 3 (C-Fam) At a recent briefing ahead of the annual Commission on the Status of Women (CSW), UN officials equated “pushback” against a pro-abortion and pro-LGBTQ agenda with the intimidation and reprisals faced by some individuals around the world who report real violations of their rights to the UN.

Such conflations were frequent throughout the event. Åsa Regnér, the Deputy Executive Director of UN Women, expressed concern about “several crises” around the world. “I’m thinking obviously about Afghanistan, but also Iran, or issues such as the overturning of Roe v. Wade, et cetera,” she said, as well as “sexual violence against women after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.”

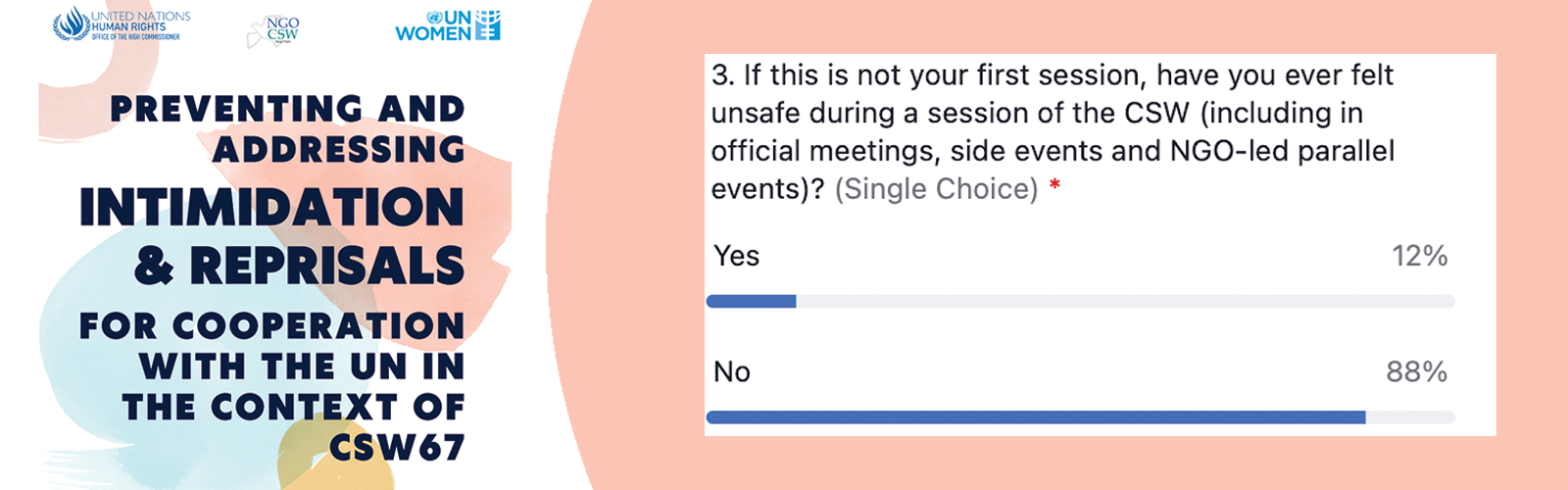

The event, which was hosted by UN Women, the New York office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, and the official CSW civil society platform, offered no specific examples of the types of threats they were seeking to prevent and address. To illustrate the severity of the issue, they cited a report issued annually by the UN Secretary-General documenting threats, attacks, surveillance, and persecution of human rights defenders attempting to work with the UN. In sharp contrast, with regard to the CSW, they spoke only of “feeling unsafe” during in-person or virtual panel discussions. Attendees to the meeting were given a poll asking if they had ever felt unsafe during a CSW session; 88 percent of them responded “no.”

Such a feeling of “safety” was purely self-reported and subjective. By way of illustration, the New York chairwoman of NGO-CSW, Houry Geudelekian, acknowledged learning “the hard way” that “even with best intentions at heart, we’re not aware of how our words are affecting the people in the room or online.”

“A lot of our audience members come in with triggers,” she added.

If activating people’s “triggers” can be equated with intimidation and reprisals, and if the head of the CSW civil society platform admits to having committed such infractions herself, then participants in discussions of contested issues may have to choose between self-censorship or accusations of committing violence.

It should be pointed out that abortion advocates usually vastly outnumber pro-lifers are UN negotiations. At the CSW itself, it is not uncommon for several thousand feminists to attend with only 100 or so pro-lifers.

The stakes are not purely rhetorical, however. At a meeting of presidents and vice presidents of the global NGO-CSW last year, one feminist leader accused C-Fam, the publisher of the Friday Fax, of threatening terrorism and suggestions were raised that C-Fam be banned from participation.

Around the world, those who stand up for internationally agreed human rights do face actual threats, arbitrary arrests, surveillance, and physical violence. Meanwhile, pro-life and pro-family organizations seeking to engage at the UN through the established civil society platforms are being accused of “sexist hate speech,” in the words of Regnér, and threatened with exclusion on that basis.

Geudelekian cited the importance of the “agreed language” negotiated by UN member states in the past, as a guide.

To the continued chagrin of many feminist activists who come to CSW every year hoping for a different outcome, the agreed language from decades of UN negotiations continues to assert that abortion is not a human right, and it is for individual governments—including the U.S. in overturning Roe—to determine the legal status of abortion for its citizens.

View online at: https://c-fam.org/friday_fax/how-un-officials-use-intimidation-to-intimidate-pro-lifers/

© 2025 C-Fam (Center for Family & Human Rights).

Permission granted for unlimited use. Credit required.

www.c-fam.org