NEW YORK, April 3 (C-Fam) In their latest attempt to get around the U.S. democratic process, abortion groups asked an international human rights panel to protect their interests against U.S. pro-life laws and policies.

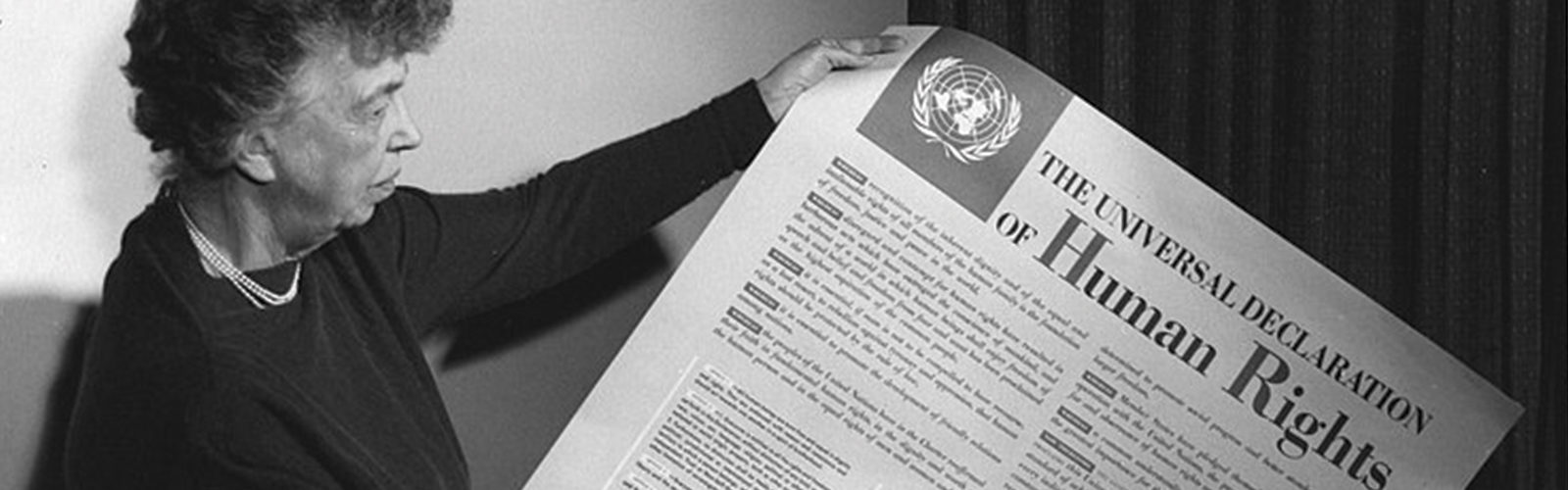

Urged by domestic and international abortion groups, the UN Human Rights Committee questioned the Trump administration about U.S. pro-life laws and policies in a March 2019 review of the nation’s human rights record. The UN committee suggested that state laws to regulate abortion violate international human rights law, including conscience protections for medical providers that are currently the law in up to 45 U.S. states.

One year on, the U.S. State Department has yet to respond to those questions, while Finland and Lesotho, who were asked questions by the committee at the same time have already replied. If the Trump administration is no longer in the White House next January, and no written response is produced by then, it could result in a Democratic U.S. administration giving vastly different responses about U.S. state laws.

The UN committee challenged President Trump’s expansion of the Mexico City Policy, which bars groups that perform or promote abortion from receiving U.S. foreign assistance. Entitled the Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance policy, the UN committee refers to it as the “global gag rule,” a disparaging nickname used by abortion groups.

The UN committee criticized an executive order issued by President Trump on religious freedom, claiming it “allows employers and insurers to make ‘conscience-based objections’ to the preventive care mandate of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and thereby restricts women’s access to reproductive care.” The order was widely seen as necessary to give relief to groups like the Little Sisters of the Poor, who were forced by the 2009 Affordable Care Act to pay for abortion and contraception against their conscience.

The UN committee also called into question state laws “which restrict women’s access to reproductive health and abortion services and create new barriers to them in practice.”

According to the committee’s interpretation of Article 6 on the right to life of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), mothers have a right to government-subsidized abortion if their unborn child is conceived by rape, their own health is in any way compromised, or their child is severely disabled. They argue that any restriction on abortion puts the lives of mothers who seek abortions in danger.

The United States ratified the ICCPR in 1991 with a reservation urging full respect of the U.S. federal system of government. To get around that federalism reservations, and the possible reversal of Roe v. Wade, Democrat lawmakers are trying to expressly incorporate the committee’s interpretation of the right to life, one that includes abortion, in U.S. law through the Reproductive Rights Act.

The questions asked by the committee mirror reports of domestic and international abortion groups to the committee. To their great alarm, over the last decade, dozens of new restrictions on abortion democratically enacted in U.S. state legislatures. According to Americans United for Life, 22 states adopted such laws in 2019.

The coronavirus pandemic has forced the committee to postpone its schedule. It is expected to have an in-person dialogue with representatives of the U.S. Government in 2021. A written answer is expected before then. Unlike this year, past written replies to the committee have been produced within just a few weeks of the committee raising its questions.

The U.S. is permitted to also dispute the committee’s views in the UN General Assembly in writing and orally, including an upcoming discussion of how to reform UN treaty bodies. The U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Human Rights, Democracy, and Labor is normally tasked with such responses.

*This article has been updated to reflect that Lesotho and Finland have replied to the Human Rights Committee list of questions, whereas the U.S. government has not.

View online at: https://c-fam.org/friday_fax/un-bureaucrats-europeans-undercut-u-s-state-pro-life-laws/

© 2024 C-Fam (Center for Family & Human Rights).

Permission granted for unlimited use. Credit required.

www.c-fam.org